Plato in Space

Charles T. Rubin

Anathem is a big book about a big topic: nothing less than the nature of the universe and of intelligence within it. The novel certainly has its share of action—but as befits its topic it is even more filled with argument. Neal Stephenson seems most interested in exploring a proposition that can be stated fairly simply: like the laws of nature it discovers, intelligence itself is the same throughout the universe. If Pythagoras discovers his theorem here, the equivalent insight will be found elsewhere. If we have Platonists, empiricists, and logical positivists, similar schools of thought will be found wherever there is intelligence. Most science fiction involving contact with aliens, which is indeed the device that moves the plot of Anathem, is implicitly premised on at least some weak form of this proposition, though none that come to mind explore the question with quite the philosophical depth of Anathem.

One important aspect of the novel is likely to be of particular interest to readers of this journal, for on Stephenson’s world of Arbre, the relationship among science, technology, and politics is, as the book opens, radically different from what prevails in our world today. Stephensonis, in this novel as always, a thoughtful and therefore thought-provoking author, and in presenting us with the arrangements on Arbre he allows us to reflect on how the motives that drive scientific and technological development relate to what can be done about the problems that arise therefrom, and on how dealing with such problems will be influenced by what we think about historical progress.

Some four millennia before Anathem’s story opens, Arbre was much like Earth today. Science and technology flourished together and in full cooperation with business, military, and government; on Arbre this period is called the Praxic Age. But then, following two great wars and a genocide (the “harbingers”), came “the Terrible Events,” a planetary catastrophe. Details are sketchy, but global climate change and the creation of a more unstable climate are certainly part of the picture. In response to what were taken to be the proven dangers of unfettered scientific research, scientists were segregated (or segregated themselves; the point is to some degree contested) from the rest of society and thenceforward live under monastic-like discipline in carefully controlled cloisters. These are known as “concents” and the natural philosophers who live within their walls are called “avout.”

(The obvious similarity to “convent” and “devout” is part of Stephenson’s effort to make this world understandable and to suggest playful parallels and similarities between it and our own. Revered scientists are given the title “Saunt”—but whereas our “Saint” implies holiness, “Saunt” is derived from “savant.” The non-scientists outside the walls of the concents are said to live in the “Sæcular” world. Moments of what we would call “insight” are called by the avout “upsight.” Many specific concepts and characters from the history of Western philosophy are given new names—so the Agora of Athens becomes the “Periklyne” on Arbre, and Occam’s razor becomes “Gardan’s steelyard.”)

The discipline of the concents limits what the avout can possess (no technology from the outside world, for example), what they can study and with what tools, what kinds of plants they can grow, and how much contact they can have with the outside world and indeed with each other. The concents of which we hear most are subdivided into “maths.” One math opens itself to information from the outside world and from other maths once a year, another every ten years, a third every hundred years, and a fourth every thousand years. Fraa (“brother”) Erasmas (known as Raz), the narrator-hero of the book, is a late teen living in a math of “Tenners.” As the book begins, it is preparing for its once-a-decade opening. So far as we know, the way of life in each math is essentially the same, built around rituals that are performed in common but with each math segregated from the others.

Men and women avout work and live together and may form various kinds of attachments. However, while the point is made repeatedly that the differences between avout and those who live in the outside world are more a matter of nurture than nature, the avout food supply contains a birth-control agent to prevent any accidental or deliberate effort to breed super-scientists. While some of the “avout” move up from one math to another when the opportunity presents itself, clearly the concents can only perpetuate themselves by bringing in people from the outside—foundlings, excess children, or by-blows of the upper class. The biggest challenge would seem to be keeping the Thousander maths going, but we eventually find that they live unusually long lives, and that abandoned infants are sometimes sent into their math so that they will not contaminate it with outside knowledge.

The Concent of Saunt Edhar on which the first sections of the book focus, like others we later learn of, is divided not only by the maths, but by a variety of sects within the maths based on philosophical divergences or different foci of study. Like our academics, these avout are relentless sectarians. A further division within the concents stems from the fact that the avout do not have any access to computer technology and Arbre’s equivalent of the Internet, so the concent has various mechanisms and tools that the avout cannot run or repair themselves; for that they are dependent on tech-savvy custodians called Ita.

Formally supervising the whole system are hierarchs, avout who have greater contact with the outside world, and over the local hierarchs stands an Inquisition that travels freely. Avout who break the rules are ordered as punishment to copy and memorize while in solitary confinement material “crafted and refined over many centuries to be nonsensical, maddening, and pointless.” Worse still, an avout could be subjected to “Anathem”—expelled entirely from the concent and “Thrown Back” into the Sæcular world. We know for certain that mathic discipline is imperfect and we have reason to suspect, particularly in relation to the rarely-seen Thousanders, that it might even be less perfect than we directly observe. Nonetheless, on the whole it seems to operate effectively.

The result of all these measures is to slow the accumulation of scientific data, and to sever the link between science and technology. So there is on Arbre no “big science” as we know it and, it would seem, little laboratory work. Over the centuries that follow the Terrible Events, various additional restrictions are placed on the mathic world, such as a ban on genetic engineering. These accommodations result from the concents being sacked when the Sæcular powers that be get too worried about what is going on inside them. However, the avout are still “on tap” for these Sæcular powers, which can call them out as necessary to solve problems that require their expertise. Raz and the other avout at Saunt Edhar’s mostly seem to study astronomy and cosmology; we are led to believe they are making observations that would have otherwise required huge particle accelerators. They have little to work with except telescopes, chalkboards, paper (from genetically engineered trees that produce paper leaves), and pen—and their own minds, which they systematically develop through memorizing and participating in various forms of more or less Socratic dialogue.

Assessing the effects of the segregation of science on the rest of the world is made difficult by the fact that we see the world beyond the concent walls through Raz’s eyes, and he is certainly a prejudiced observer to begin with—although he becomes less so as his experience widens. Still, the worst one might say is that it is in many respects a somewhat degraded version of our own world today. The intellectual level of the outside world is not high, despite the fact that the one-year maths serve as colleges for the upper classes. Commercially and militarily motivated technological change occurs, even though the artisan class is not interested in the newest technology but in being able to comprehend, develop, adapt, and repair its own existing tools. The artisans we come to know best would be very unhappy to be as dependent on anyone as the avout are on the Ita. Mass culture is somewhat lower than our own, literacy more rare, religion (which from the avout point of view is part of the “Sæcular” world) perhaps more powerful at least in some time periods. (On Arbre, science and religion share a common father, which allows Stephenson to present what is, for a work of science fiction, a highly nuanced picture of the role of religion in life and its relationship to science. But this topic would be a fit theme for discussion all on its own.) Despite the fact—or perhaps because of it?—that there is a chemical in the food supply that makes people outside the concents feel good, the social and political world does not seem very stable—although the appearance of instability may reflect the telescoping effect of the very long view of history taken by the avout. Still, when Raz is called upon to leave his concent and travel on the outside, he observes a good deal more decaying than being built up. He himself notes that this kind of ebb and flow is cyclical, like the unstable climate.

What we can say for sure is that this strong division between the mathic and the Sæcular world proves to be highly stable; the arrangement has been in existence for well over three thousand years. What is required to have that stability is cutting off scientists from the outside world and to some extent from each other, cutting them off from most kinds of useful technology and technological development from them, and having a non-scientific culture that is more or less hostile to them by default. The scientists must believe that on balance their isolation is for their own good, and there must be a way for them to exercise their inquisitive minds. If, however noteworthy the subtle likenesses between concent life and our system of higher learning, we find it hard to imagine that the system Stephenson lays out could possibly come to pass in our world, that may just be because in our world the burden of guilt for “Terrible Events” we are still mostly imagining—from disastrous climate change to nuclear holocaust—has not yet been assumed by, or shackled upon, scientific shoulders.

But this stable arrangement contains both the good news and the bad news of Arbre’s history compared with our own. The “harbingers” of the Terrible Events sound suspiciously like our twentieth century. Assuming even a rough equivalence between Earth and Arbre years, Arbre represents a rather distant human future. The bad news is that Arbre, with only a few notable exceptions, has certainly not achieved anything like the extraordinary developments that science and technology seem to promise us today, let alone what science fiction routinely expects of so distant a future. With few exceptions, there is no radical extension of the human lifespan or of human capabilities. Arbre has not colonized and environmentally engineered other planets. The fact that Sæcular culture three millennia on is a somewhat degraded version of our own might even suggest that it is stuck in a kind of dark age. The good news is that there seem to have been no further “terrible events,” and even the last, longest, and worst of the sacks ended over eight centuries before the book opens.

So the mathic system “works” in the sense that the restriction of scientific research and its separation from technology creates the most stable age in Arbre’s history, even if everything is not all sweetness and light. We should perhaps not be surprised that such stability has costs of its own. But for the avout these costs are perhaps not as high as we might think. It is true that the sacks exact a terrible cost, particularly the last one. It is true that some avout chafe at restrictions and are disciplined or expelled for breaking rules. But the avout who actually engage in research (not all do so; the less able are shunted off into useful work around the concent) do so with ingenuity heightened by their limited resources and the intense focus that follows from their lack of distraction. Their discipline produces orderly habits of thought and action, along with a fair degree of comradely devotion to their brothers and sisters, sects, maths, and concents. Within the broad limits imposed on them, they seem to have freedom to choose to study whatever inquiries interest them, unmolested by disapproving non-scientists, and uninfluenced by commercial motives or external funding streams (although there is politicking among the various sects). Finally, they have a patience that comes from having a very long-term perspective on the significanceof their own contributions within the larger mathic effort at understanding the world.

Stephenson seems to think that a certain kind of person, with a certain kind of education, will find ways to answer the questions that interest him whatever the circumstances; for example, without calculating machines the avout have developed the ability to model calculations using songs. The fact that Stephenson calls the avout “theors” is also significant—their intellectual efforts are far more like the ancient science that was akin to contemplation than Baconian science directed at conquest, doing and making for immediately useful even if charitable purposes. This difference between theors and our scientists is only highlighted by the fact that the theors are the guardians of Arbre’s philosophical heritage. The intellectual and historical underpinnings of their efforts are very much a living part of what they do as theors—they are not just “gen-ed” add-ons, as they are for so many of our scientists-in-training. So we are not surprised when one character remarks that the avout spend their lives learning how to learn; they specialize without becoming narrow specialists. In the scheme of things, that is unlikely to strike many of us as the worst of fates, and suggests how the mathic system preserves what is best in the spirit of scientific inquiry as we know it.

That is not to say that the mathic system represents a model we should attempt to emulate in order to avoid our own version of the Terrible Events. But neither should we assume that the three thousand years of relative stability on Arbre made possible by the mathic system, including its costs, are just an arbitrary exercise of Stephenson’s imagination. We can see it as a thought experiment if we compare it with our usual way of doing things. On those rare occasions when those of our intellectuals who think at all about restraining developments in science and technology do so, they unsurprisingly think first in terms of the accustomed tools of a liberal democratic order that seeks to be minimally invasive in such matters: government regulatory oversight, or ethics norms voluntarily developed by professional organizations and adhered to by their members—classic parchment barriers. Stephenson would certainly not be the first to wonder whether such kid-glove measures are proportionate to the dangers threatened by greatly increasing our powers over nature and each other. His more thought-provoking contribution is the suggestion that such measures also may not do justice to the deep and abiding motive behind such research and development: the desire to know. Aristotle may be correct that all men desire by nature to know, but surely the passion is more powerful and developed in some than in others. Can government paperwork and ethics codes really provide a serious bulwark against those for whom the desire to know is their master passion?

Speaking broadly, we know that one of the tendencies of modern political arrangements is to make ethical restraint a matter of individual choice, at least to the extent compatible with public order and safety. Although Tocqueville’s concerns about the tyranny of the majority cannot be dismissed out of hand, liberal democracies rightly pride themselves on their avoidance of the ruthless enforcement of beliefs and norms of the sort found in secular or religious totalitarianism. Still, we know from one of Stephenson’s previous books, The Diamond Age (1995), that he is aware of the potentially corrosive moral effects of the very democratic principle “let each do as he pleases.” There is a sense in which modern liberal political arrangements wish to have ethical citizens without having an ethos, a publicly prescribed way of life for those citizens. This project would have seemed paradoxical or impossible to the ancients, who believed that ethics needed the careful support and habituation of institutions “with teeth in them,” to use Leo Strauss’s memorable phrase. And such a system is just what the mathic order represents. The discipline of the avout is written in a book but does not just happen from reading that book; it is lived and reinforced moment to moment by the very structure of their days, their possessions, their activities. If even then the system is imperfect and some avout place their desire to know above the rules of the community, then how much less restraint can we expect from less stringent measures within the framework of a more individualistic culture, and one where the already powerful desire to know will be freely mixed with other powerful desires the avout are less subject to—say, for material goods or public influence?

If part of friendship is avoiding discussing the defects of one’s friends, some friends of liberal democracy may feel it is not polite to confront this dilemma. Everybody understands, they might say, that neither fettered nor unfettered scientific and technological development is a free lunch, and that the costs and benefits of either course of action will be distributed unevenly. Our rather mild regimes of restraint stem from the judgment that on balance less control has larger benefits because it leads to more progress, and that the way you solve the problems of any one stage of historical progress is to press beyond them to the next stage. Progress may open the door to “terrible events,” but that just means we have to make progress all the faster in order to avoid them.

Viewed this way, progress is an infinite historical task, without a clear goal or purpose towards which to advance; one might wonder, then, why we call it “progress” and not simply “change.” But that we live in and should want to live in a progressive world is a crucial element of our narrative about ourselves. At various points in the story, Anathem suggests that a life well lived requires some such story to make it meaningful, some sense of purpose. Historical progress is the story that makes us reluctant to limit developments in science and technology. Stephenson’s treatment of the relationship of religion and science on Arbre suggests that, while it is dangerous to have no story at all, it is also problematic if one adheres dogmatically to the sole truth of one’s own story. Anathem raises questions about whether or to what extent this thing called progress really exists.

Anathem is filled with cycles; the analemma on the book jacket is a well-chosen graphic element. With their long-range perspective, the avout see cycles everywhere. Polar ice expands and contracts, cities grow and shrink, empires and beliefs rise and fall. The avout cyclically open and close their maths to the outside world, and inside the concent walls their days are structured by repeating rituals performed around a huge (non-digital) clock. They are aware that it is harder than it seems for something new to arise under the sun. A sect among them, the Lorites, specializes in pointing out when apparently new ideas are really just repetitions of old and otherwise forgotten ideas, and Lorites seem to have no lack of work to do. The intensely sectarian structure within the maths is testimony to just how hard it is to get beyond certain fundamental assumptions or predispositions.

Yet against this cyclical view of events, the book ends on an apparently progressive note. In order to be better prepared for future visitations by potentially hostile aliens with superior technology, Sæcular and avout have agreed to govern Arbre as two Magisteria. But here a complex and ambiguous aspect of the story must be noted. For it is not impossible that elements among the avout themselves helped bring about this crisis and, with the cooperation of a shadowy group of quasi-avout operating in the Sæcular world, shaped its course. We know for a fact that the Thousanders can manipulate the course of events (although in the cosmology of the book that is not the right way to describe their ability) and that such manipulation is crucial at a critical moment in the story; there are alternate timelines in alternate universes that have less happy outcomes. Raz at least is willing to take seriously the possibility that this shadowy group of avouts engineered the crisis by summoning the aliens, all with the intention of bringing the mathic age of scientific segregation to a close.

Nobody speaks against this new world order and some are clearly excited by it. As the book closes, we see Raz establishing a new concent. Predicated on this new avout-Sæcular cooperation, it will not be closed off from the world in the old mathic way. Yet it will still have walls, and the walls are already being laid out with an eye to their defensibility and with arched openings that could readily be turned into the closed gates that had defined the mathic concents. Diarchies are notoriously unstable.

Beyond that problem, ought we not expect that avout and Sæcular working together to meet some unknown contingency will develop very dangerous technologies? The timeline-manipulating Thousanders and their allies may have a good deal of work ahead of them if this second age of science and technology is not to end as disastrously as the first one. For us, it should be a sobering lesson if such godlike power is what it would take to maintain stability and prevent a repetition of the Terrible Events. Without that godlike power, it would seem, we should just expect that old patterns will be repeated.

The overarching metaphysic and cosmology of Anathem may suggest that this seeming anti-progressivism is not the last word. Raz is a member of a quasi-Platonic sect that believes that our ideas are reflections of Ideas; he joins their ranks despite the fact that they are widely looked down upon for holding what seems to be a suspiciously religious point of view (in our terms: the realm of Ideas sounds too much like heaven). Yet events more and more seem to vindicate their perspective, eventually allowing speculation that the universe in which Arbre exists may be a cosmos “closer” to the ultimate world of Ideas than the alternative cosmi from which the aliens prove to have come. It might be tempting, then, to see the cycles of Arbre as moments in a larger ascending spiral moving towards some ultimate truth.

Even if that view were correct, it would already be distinguished from historical progress understood as an infinite task without settled purpose or direction. However, it is not clear that the book’s quasi-Platonism makes the ascending spiral the appropriate image. Towards the very end of the book, when Raz’s views of at least some of Arbre’s religions have softened, he speaks of one preacher’s “amazing, exasperating sermons, filled with wisdom and upsight and human truths, fettered to a cosmographical scheme that had been blown out of the water four thousand years ago.” Yet perhaps a good Platonist should not be amazed or exasperated. Even if it is simply a human possibility—that is, possible always and everywhere—to grasp the truth, to have “upsight” into some of the truth does not mean upsight into all of it. To use the favorite example of the book, the Pythagorean theorem is an Idea that is true always and everywhere, and may be grasped always and everywhere, without complete knowledge of the whole of which it is a part. “Progress” occurs, one might say, when one moves from not knowing it to knowing it, but that progress has nothing to do with time or historical development; indeed an enigmatic Thousander suggests that time does not even exist, which would leave historical progress an illusion within an illusion.

In themselves, these are just the sort of arcane speculations that are quite suitable for science fiction. But as was the case with the obviously impractical concents, they are speculations that can make us wonder whether there are not equally arcane speculations upon which our more accustomed ways of thinking are built. The important truism that “you can’t stop progress” is easy enough to say, but understanding what it actually means is another matter—as is the question of whether it is true.

Anathem presents us with a familiar unfamiliar world and in so doing opens a door to asking such questions. We think we know the best ways, if necessary, to limit developments of science and technology, but Stephenson makes us wonder whether our easygoing ethical individualism is adequate to both our growing power over nature and ourselves, and to the force and dignity of the impulse to know that stands behind our science. We think we know what historical progress means, but Anathem makes us wonder whether progress without truth is anything more than change, and whether truth does not render progress superfluous. Is not wonder the beginning of philosophy?

Charles T. Rubin, a New Atlantis contributing editor, is an associate professor of political science at Duquesne University.

Charles T. Rubin, "Plato in Space," The New Atlantis, Summer 2009, pp. 59-68.

http://www.thenewatlantis.com/

A

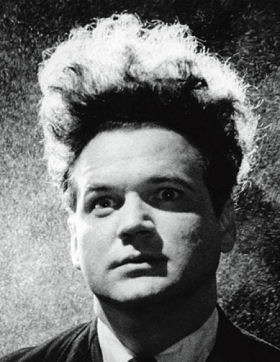

A  Psychologists at the University of California - Santa Barbara and the University of British Columbia have found that exposure to surrealism, by say, reading a book by Franz Kafka or watching a film by director David Lynch, enhances the cognitive mechanisms that oversee the implicit learning functions in the brain. The research was reported in the journal Psychological Science.

Psychologists at the University of California - Santa Barbara and the University of British Columbia have found that exposure to surrealism, by say, reading a book by Franz Kafka or watching a film by director David Lynch, enhances the cognitive mechanisms that oversee the implicit learning functions in the brain. The research was reported in the journal Psychological Science.